The recent death of 926F of the Lamar Canyon Pack has got me thinking back on all the individual wolves I have had the honor to observe and get to know over the years. I feel so fortunate having been able to spend the last decade and a half watching many of Yellowstone’s wolves—not only because they are representatives of an interesting species—but also because they are each specific, unique individuals.

Even if we are not out there every day, watching, recording, sculpting, the wolves are still part of our landscape. Yellowstone gives us the remarkable ability to follow individual creatures, to know their life stories, to learn from them, as well to tell our own stories about them. And because Yellowstone wolves have been observed since the beginning of the reintroduction effort, it’s possible to know a lot about their family lineage and stories from the very beginning. That’s an incredible thing, and one for which I am very grateful. This is also the reason that it is so hard to see individual wolves—like 926F—go.

With the visibility of 926F and other members of the Lamar pack, you really get to see how they interrelate with the landscape and each other, and with humans both in and out of the park. That interaction with humans can be such a double-edged sword; while their visibility and relative comfort around people helps inspire many advocates for their protection, it is also what makes them vulnerable when they step outside the park.

Specifically for the Lamar canyon pack, it was wonderful to hear that they had returned to the park and the valley after a long absence (I hadn’t seen them for a broad swath of the spring and summer), and with, of all things, five puppies in tow! What a phoenix story: nobody knew if the pack would even survive, and then they returned with the next generation at their side. And now with one bullet, the destruction of their family seems closer than ever.

I remember my grandmother forbidding me to shoot the squirrels and the mourning doves around the feeder as a boy. It’s not an uncommon thing for hunters to refrain from shooting animals that are around their home because we find some solace in their company and recognize that even if we are impacting them we don’t want to do it in those places we call home. We need to learn to extend our “home” beyond the walls in which we reside and the property boundary outside. Home has to mean something more broad, elemental and timeless. Our actions have impacts; this is painfully clear when you witness the effects of removing an alpha wolf from their pack. It’s important to be aware of the effects of our actions so that we can evaluate whether what we’re doing is in line with our values.

I think the highest order service we can provide on behalf of wolves—or any animal—is to tell their stories, whether through writing, photography, or—in my case— artwork. We’re deeply in need of new narratives about wild places and their denizens so that we can learn how to care for things in the ways they deserve. We must become better stewards of the land. We are ruining our environment at a dizzying pace. It becomes a lot harder to ruin something when you have a relationship with it. As in the case of 926F, we follow animals we have come to know through our own stories and through others’ stories. In this way, we keep them alive.

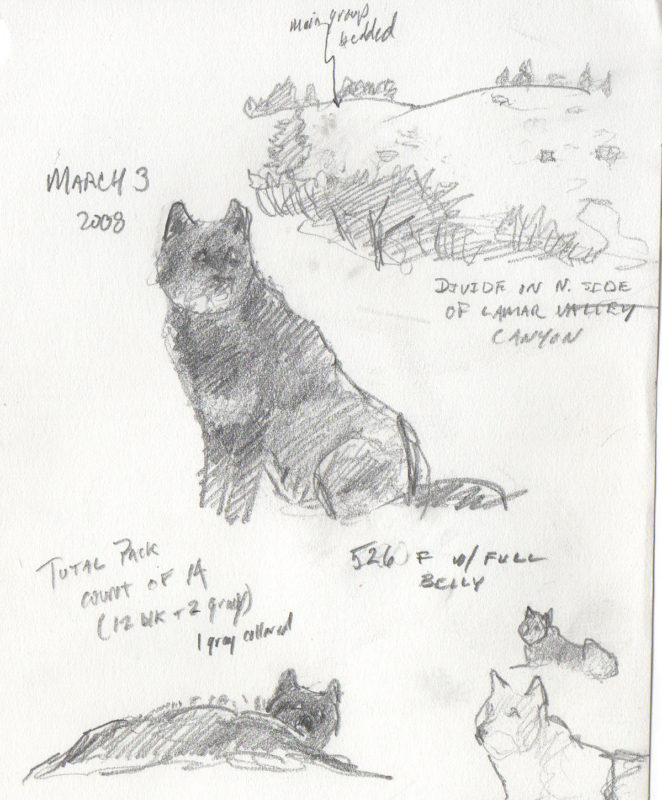

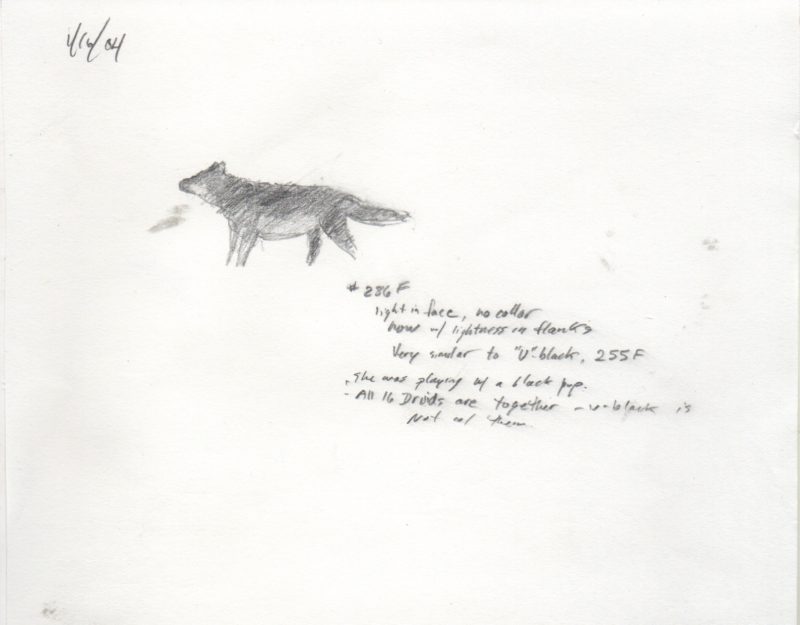

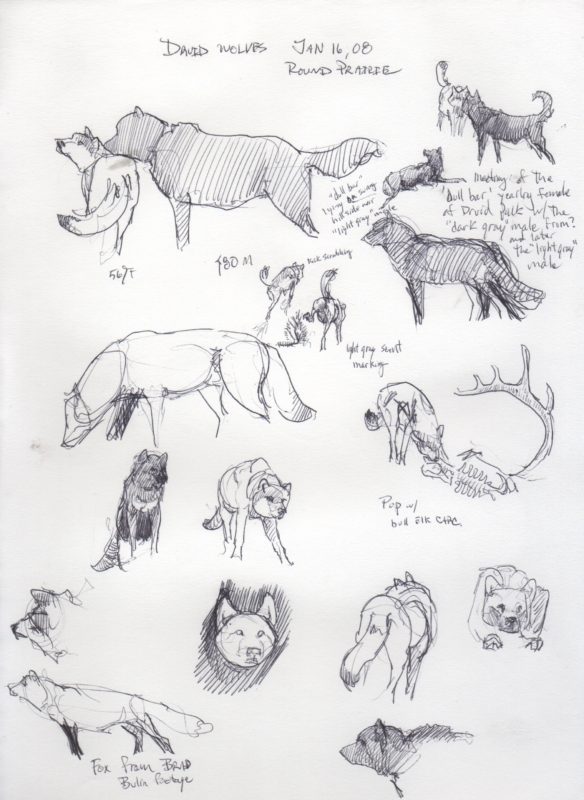

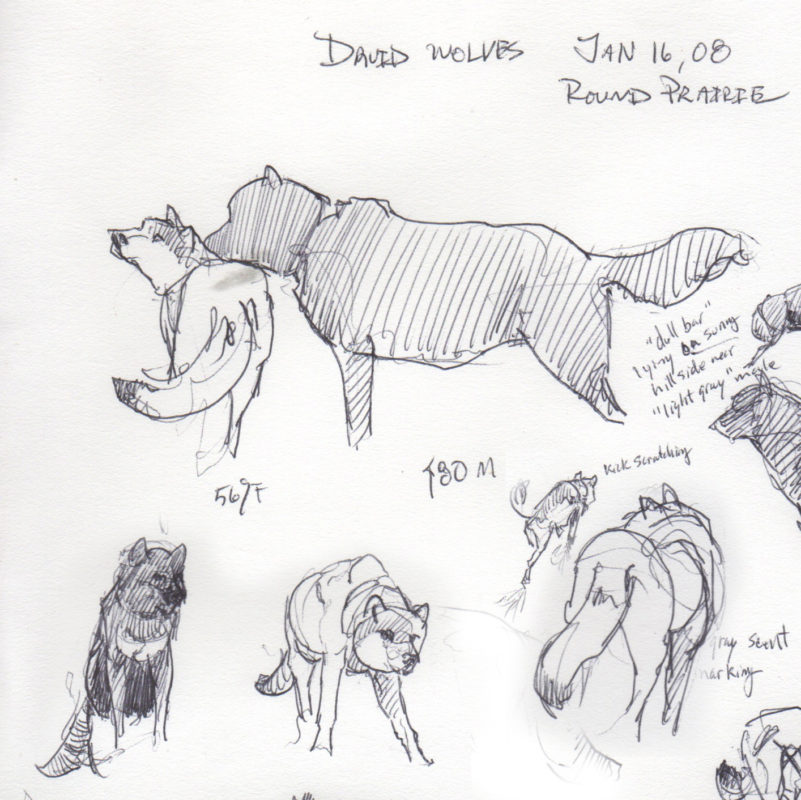

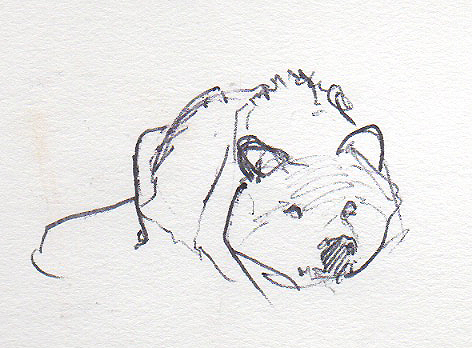

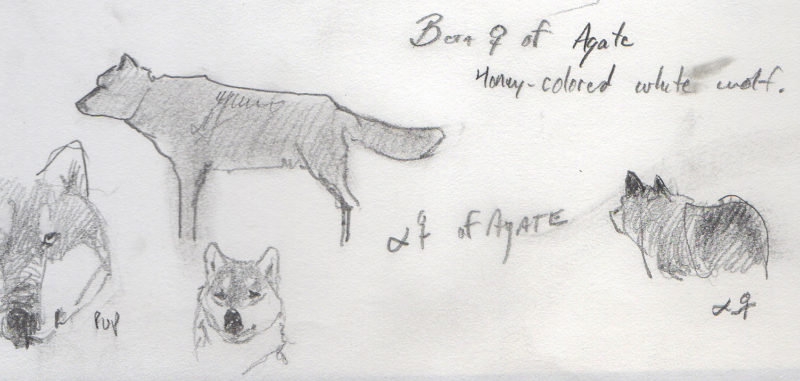

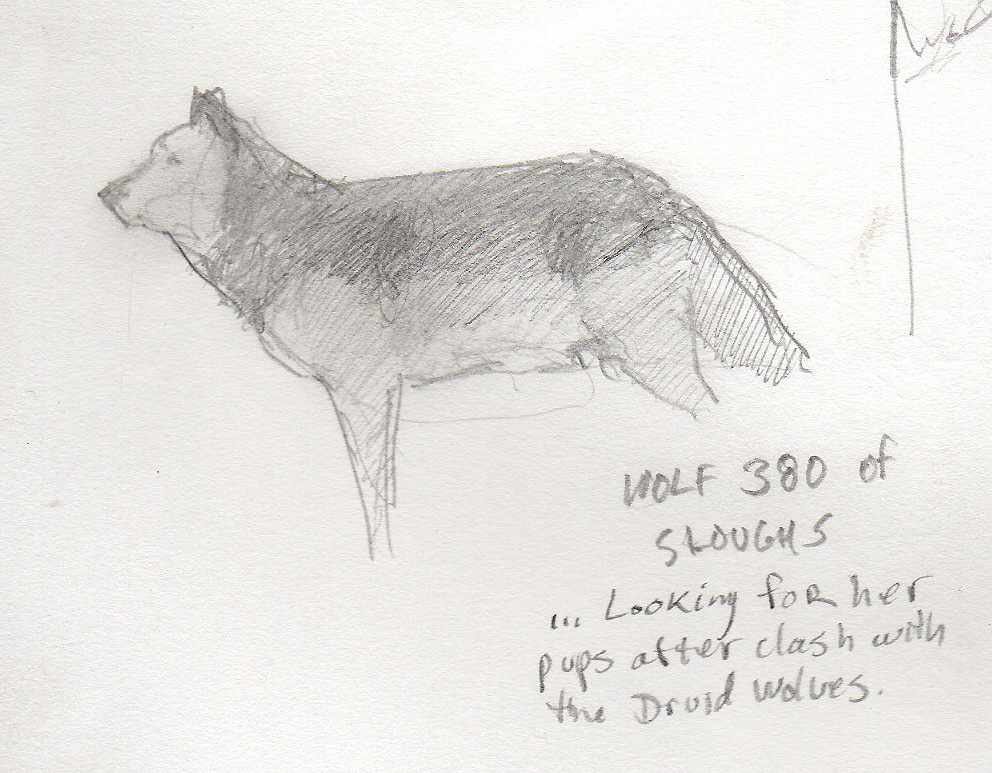

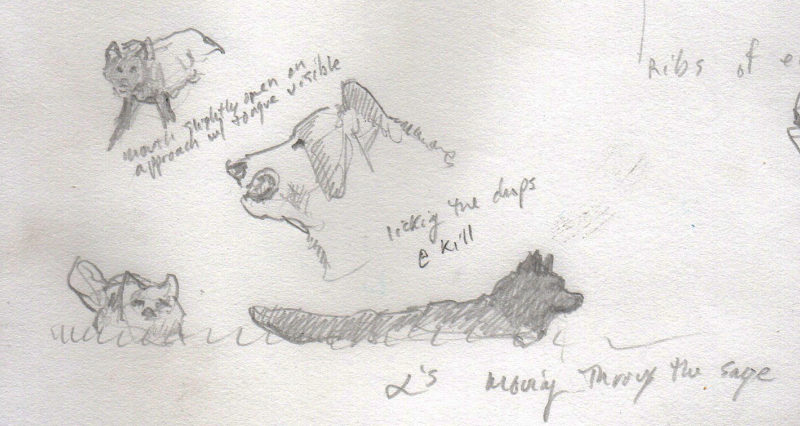

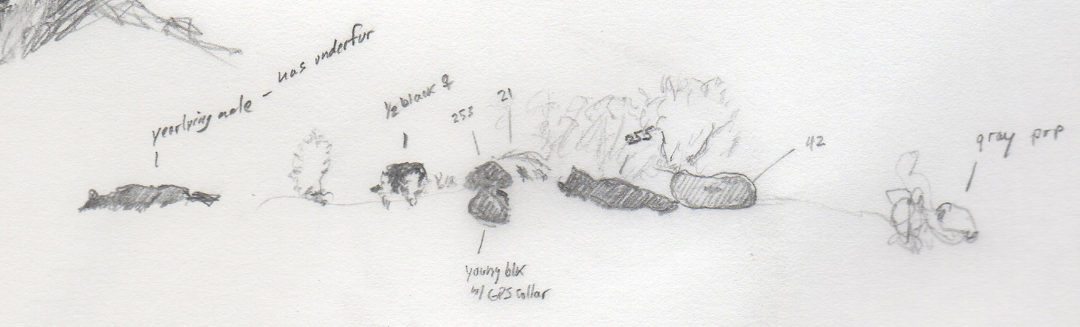

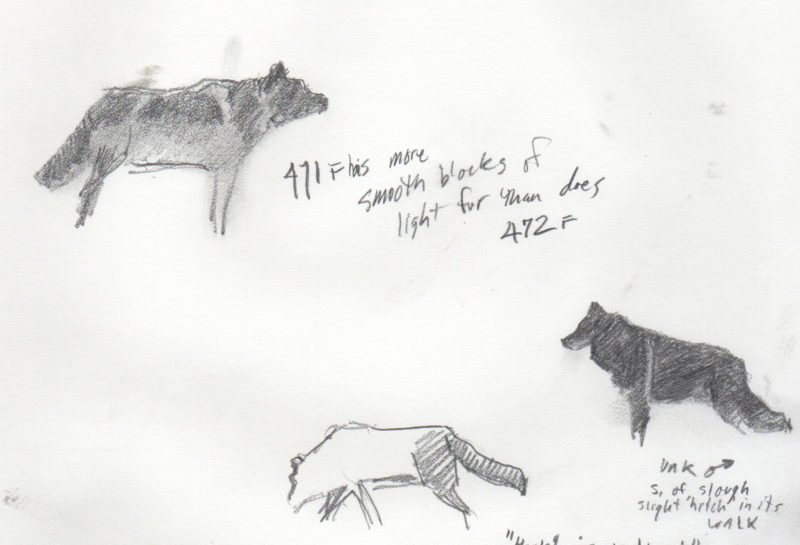

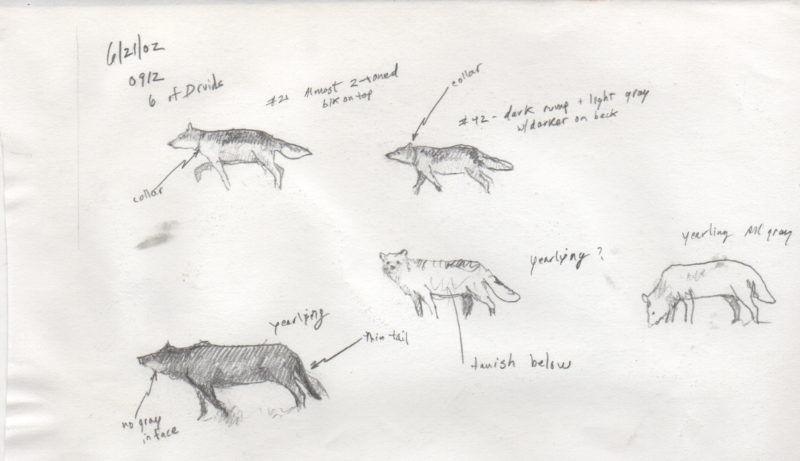

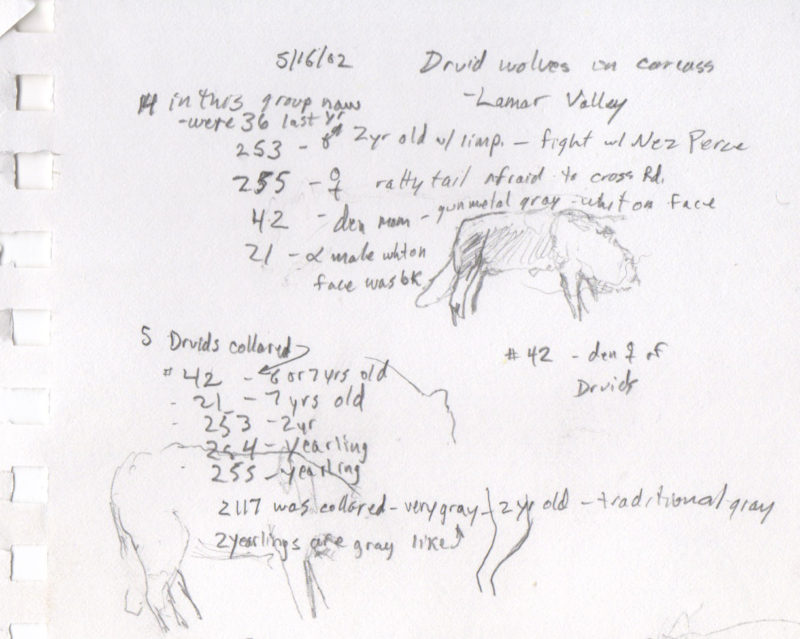

Drawing and sculpting these animals is my way of telling their stories. The purpose of my pages and pages and books and books of sketches is to create shorthand reminders for later contemplation and development into sculptures or spoken stories. They are reminders of specific encounters, particular days, particular individuals, gestures, behaviors, thoughts and intentions.

Why sculpture? Sculpture has the capacity to bring an outside entity, with it’s full power and individual spirit, into a distant space no matter how far removed from the source. People don’t name paintings, but they do name sculptures; they have a presence about them that lends itself to its own form of physical storytelling. I want to provide a connection between “our” world and “theirs” in hopes of sparking a deeper connection with nature and reduce the feeling of “otherness.” Storytelling is a deeply human way of sharing experiences, and is how we progress; we gain a broader understanding of the world and and earn a better way of existence through the power of stories.

I look back fondly at this sampling of wolf sketches from over the years. Are there any wolves you recognize? The sculptures that resulted from my many sketches are very meaningful to me – ones of 21 and 42 with their bumpy ascents to leadership–all the while fading from pure black to pure gray, the indomitable spirit of ’06, the essence of the “Hayden Valley Pack female”, her daughter “the Canyon female” manifested in the White Lady. They’re much more than “just wolves”. They are unique and remarkable individuals. Along with 926F, I feel deeply honored to have gotten a glimpse of their lives. So sad to see you go.